How to do things with data: Creative re-use of SMK’s digitized collection

Aiming for “radical openness” we’ve published SMK collection data in the most liberal fashion we could think of. One aspirational goal is creative re-use, so what happened in practice?

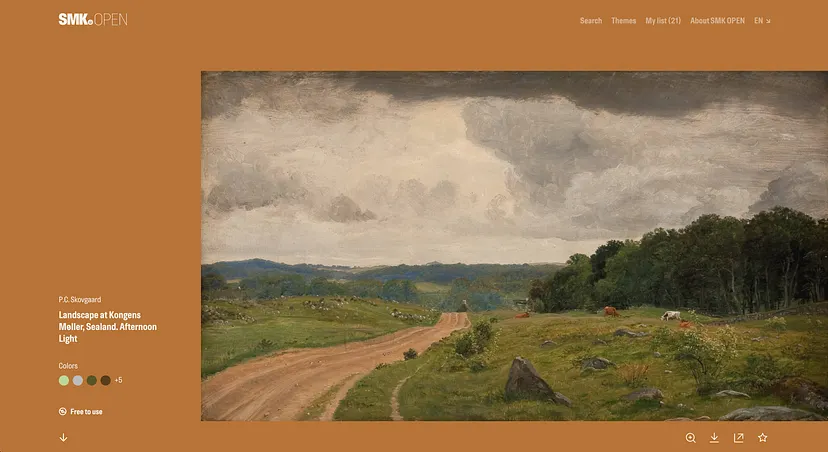

On open.smk.dk users can explore the SMK collection and download material for re-use

On open.smk.dk users can explore the SMK collection and download material for re-use

Practically all SMK collection data including images (to the extent allowed by copyright) gets instantly published for free use — for humans on open.smk.dk and for machines via our API. The goal is maximum openness in order to increase the value and usefulness of the museum’s collection.

In the OpenGlam spirit we encourage good old-fashioned use. We invite everybody to consult the vast trove of art historical data, to explore connections between artworks, and to download photos and 3D models for use in everything from school assignments to presentations, PhD theses, and books. This invitation was picked up, as underlined for instance by considerable interest in Erik Henningsen’s social realist painting Evicted Tenants from 1892 — not least from primary and high school students delving into the so-called Modern Breakthrough.

But we also strongly encourage re-use, the creative appropriation of the SMK collection for the user’s own purposes. We often talk of the collection as creative raw material and the data as Lego bricks (flexible, open) as opposed to cathedrals (nice but non-configurable). This implies surrendering all control in the sense that we do not presume to know what the data can be used for nor presume to specify what it should be used for.

As you can imagine, such art data laizzes-faire leads not to order but to a chaotic jungle landscape most of which we never see. But news of some initiatives do reach us and here are some recent examples that stand out.

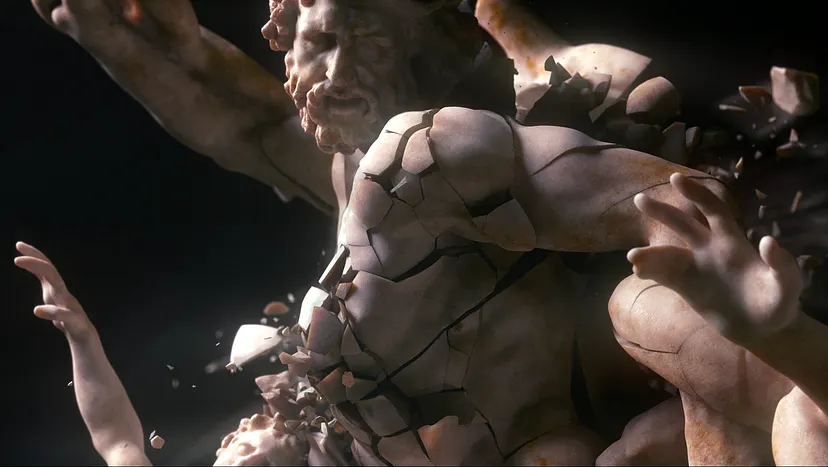

Award-winning short film

As the Covid pandemic raged, Italian film-maker Lucio Arese mixed 3D scans of SMK sculptures into the multiple-award-winning short film Les Dieux Changeants (The Gods are Changing). It’s Nietzsche meets Chopin meets The Royal Cast Collection, powered by our collaboration with 3D repository MyMiniFactory. For context and details see my colleague Merete Sanderhoff’s interview with Arese.

The Laocoon group is destroyed in Lucio Arese’s short film

The Laocoon group is destroyed in Lucio Arese’s short film

Fanciful electronic music Instagram mashups

In Germany, Ansgar Te AKA Captain Cosmotic mixes electronic music with classical painting with style, humor and wondrously counterfactual captions. The good captain has played with several SMK artworks such as Peter Ilsted’s At the Piano (reworked), Carl Bloch’s Still Life with Fish (reworked), and Peder Balke’s Tree in a Wintry Forest (reworked).

Carl Bloch’s Still Life with Fish a la Captain Cosmotic

Carl Bloch’s Still Life with Fish a la Captain Cosmotic

Image recognition the API way

Danish museum art recognition app Vizgu lets you point your phone camera at an SMK artwork to instantly get more info. The magic happens by a direct connection to our API instead of (as would have been the traditional way) someone manually inputting all relevant data into yet another system.

Using the Vizgu app at SMK

Using the Vizgu app at SMK

3D models in all shapes and forms

Since uploading our first experimental batch of 3D scans to Sketchfab in 2016 and subsequently building up a respectable digital collection on MyMiniFactory, it’s been obvious that interest is massive. Our models are viewed but also downloaded, printed, and integrated into creative projects of all scales. We work closely with Jon Beck of Scan the World to expand our offering (thanks, Jon!) and are carefully (i.e. slowly) working to set up our own internal infrastructure for producing and storing 3D files.

Copy of Caryatid C, Erechtheion of the Acropolis at MyMiniFactory

Copy of Caryatid C, Erechtheion of the Acropolis at MyMiniFactory

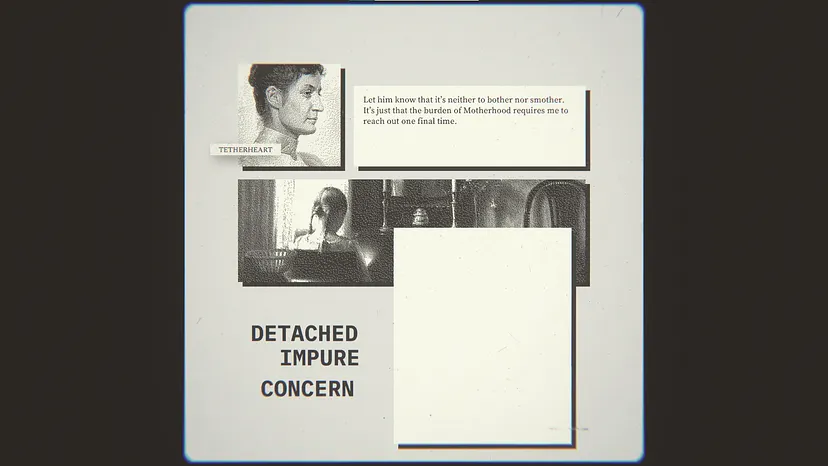

19th century painting on Steam

Presenting itself enticingly as a ‘Romancepunk, typing-game tragedy’, the Danish PC game Inkslinger [link no longer active] used 19th century paintings from SMK’s collection for its visuals. It’s a strange and haunting experience available through the Steam gaming platform.

Screenshot from Inkslinger

Screenshot from Inkslinger

Atmospheric TV screen backdrops

The makers of Netflix’ Alias Grace (based on Margaret Atwood’s novel) turned to SMK Open [link awaits] when decorating walls of their 19th century manor houses. Usable without restriction, it suddenly seemed as if British nobility were dedicated fans of the Danish Golden Age of painting.

Christen Købke’s Morning View of Østerbro from 1836 adorns a manor house wall in Alias Grace.

Christen Købke’s Morning View of Østerbro from 1836 adorns a manor house wall in Alias Grace.

Danish crime series Forhøret (The Interrogation) actually also used The Fall of the Titans to illustrate the ascent to the underworld in the form of a depravated subterranean Copenhagen nightclub.

The Fall of the Titans marks the entrance to a night club.

The Fall of the Titans marks the entrance to a night club.

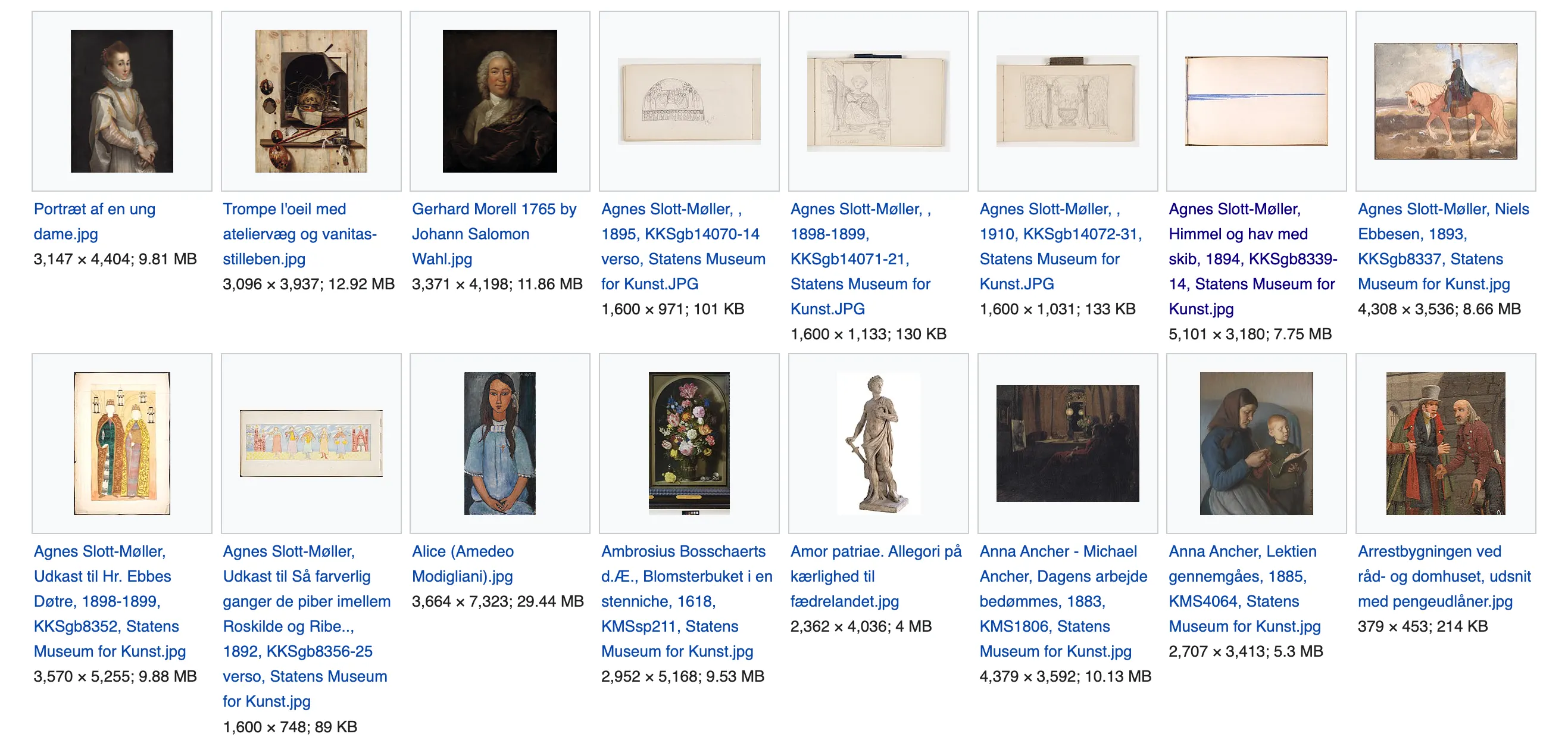

To Wikipedia and beyond

Easy access and clear licensing has enabled Wikipedians to add a considerable number of SMK artworks to the Wikimedia Commons repository (where media files for Wikipedia live). It’s an inspiring and truly useful collaboration and our next planned step is setting up a system for mass upload which can also handle changes to our core data.

SMK art on Wikimedia Commons

SMK art on Wikimedia Commons

Old art becoming new art

Thankfully — if perhaps unsurprisingly — free access to centuries of art has also directly inspired new artworks. Danish artist Amalie Smith’s Enter is a poetic meditation on the digitized SMK collection, and Ida Kvetny has reworked SMK 3D models into her wild-growing XR projects.

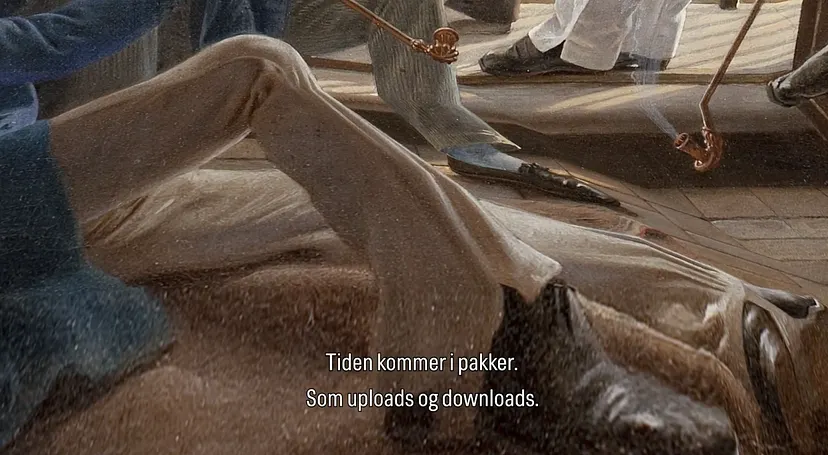

Screenshot from Amalie Smith’s Enter

Screenshot from Amalie Smith’s Enter

Screenshot from Ida Kvetny’s Hermes [link no longer active]

Screenshot from Ida Kvetny’s Hermes [link no longer active]

Not to mention…

The examples above show a wide range of uses but are merely examples. SMK art can be experienced in its full original glory at the physical main museum in Copenhagen (or at The Royal Cast Collection or in SMK Thy) but through our open access work has also been made decidedly useful (or, if you will, re-useful).

Good people have accepted the invitation to reinterpret and re-use our art history and the results range from the weird to the downright inspiring. Friends, thanks for all the pixels and do keep up the good work!